There is a small, stubborn myth that older generations are slow to admit error and even slower to change. I have watched this narrative crop up in think pieces and comment threads as if age itself breeds stubbornness. The truth is messier and more interesting. Older people respond to mistakes in ways shaped by long experience emotion regulation and an often unglamorous hunger for practical truth rather than spectacle. That nuance matters because how we learn across a lifetime alters family dynamics workplaces and public culture.

Not denial but filtering

When a person who has lived decades slips up the response is rarely a dramatic mea culpa staged for applause. Older adults more often choose to filter the fallout. Filtering is not evasion. It is a selective engagement with reality aimed at damage limitation and future stability. I have seen grandparents correct a financial bungling by quietly reallocating funds and moving on. I have seen retired managers acknowledge a poor hiring decision and then focus on mentoring replacement talent rather than lingering in regret.

Why that filter is not the same as forgetfulness

Psychological research offers a clue. As people age they appear to shift priorities toward emotional balance and away from needless friction. This is not a moral failing or an avoidance technique in the lazy sense. It is a strategy grounded in how time and perspective reframe consequences. The work of Laura Carstensen and colleagues shows that older adults often attend more to emotionally positive information and practice antecedent emotion regulation. That can mean they let some slights die for the sake of a calmer life but it can also mean they mobilise attention precisely where it matters most to prevent repeat errors.

Humans are, to the best of our knowledge, the only species that monitors time left throughout our lives.

Laura L. Carstensen Fairleigh S Dickinson Jr Professor in Public Policy Professor of Psychology Director Stanford Center on Longevity Stanford University

Correction over dramatics

One startling finding from cognitive science is that older adults can be better at correcting mistakes than younger adults. They do not always learn faster across all domains yet when it comes to updating factual errors they can outperform younger people. That tendency reveals a moral of sorts. For older generations the aim is often truth and stability not the performance of humility.

The take home message is that there are some things that older adults can learn extremely well even better than young adults. Correcting their factual errors all of their errors is one of them.

Janet Metcalfe Professor of Psychology and of Neurobiology and Behavior Columbia University

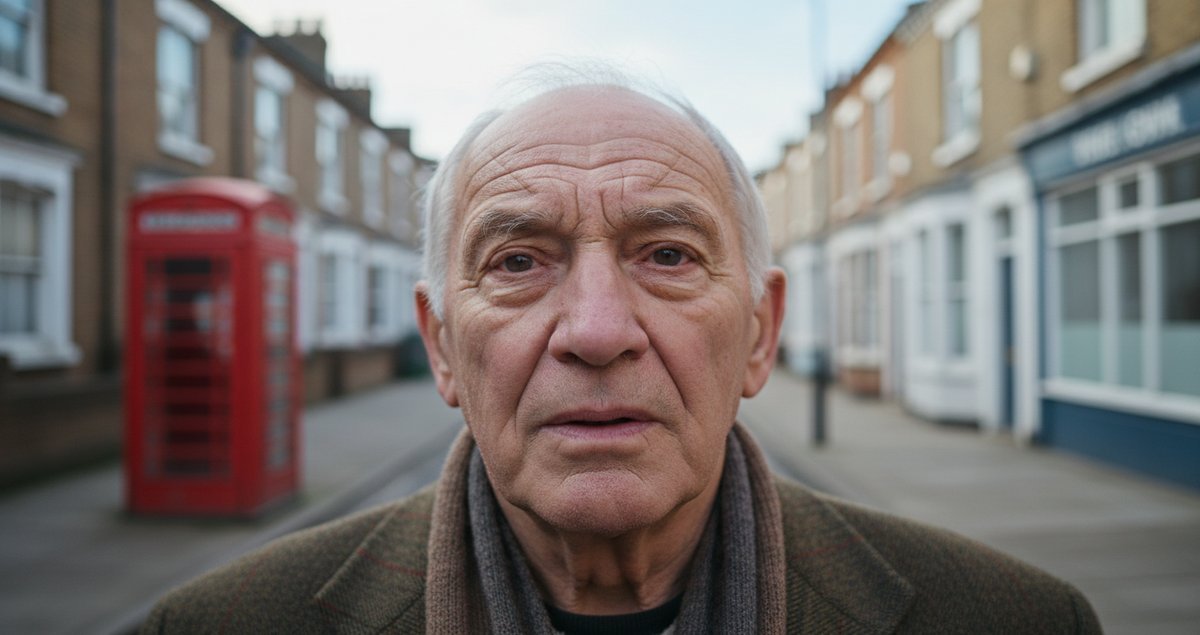

Seen in the wild

I once interviewed a seventy two year old volunteer at a community centre who had mistakenly double booked a lunch for vulnerable people. He did not post a video about his mistake. He called the kitchen apologised reorganised menus and spent the afternoon on the phones. There was no public catharsis. There was a tidy fix and a later quiet lesson for the rota system. That kind of response often goes unnoticed because our media culture prizes theatrical confession and viral contrition.

Regret as a teacher not a sentence

Regret in older adults tends to be complex. It is smaller in volume than commonly imagined yet more focused in content. Instead of a broad sense of failure older people tend to hold tightly to a few precise regrets and then use those to rearrange future behaviour. The result is not a continuous fretting but a methodical reallocation of attention. That is how lifetime learning accumulates.

Notice the contrast with how younger people often process error. The young can be all or nothing. A single mistake can feel like existential evidence of unworthiness. Older people have earned a more forgiving map of themselves through repeated missteps. That does not mean they never feel shame. It means shame is more likely to be a signal for recalibration than a permanent indictment.

Social choreography matters

Older generations also behave differently because the social stakes are arranged differently. Responsibilities often include caretaking legacy and reputational continuity. If you are seen to overreact publicly you risk fracturing relationships that took years to build. So many responses are tactical. People pick battles. They measure what to admit to whom and what to repair immediately. These decisions can look calculating but they are often pragmatic attempts to prioritise repair where it truly matters.

When silence isn’t culpable

Sometimes silence after a mistake is moral discretion. Silence can spare trauma prevent amplification and allow time for meaningful restitution. That is not the same as deception. When the balance of harm is low and the cost of an announcement high older people will sometimes choose restraint. That choice irritates our expectation for public confession but it bears examination because the alternative is performative scarlet letters that create theatre rather than restoration.

Structural advantage and blind spots

Do older adults always handle mistakes better? Of course not. Long experience can be a double edged sword. Habit and identity sometimes calcify into a refusal to change. The same decades that create better pattern detection can also produce blind spots. The key is that older people have both strategies that work and strategies that fail. They often know which mistakes deserve attention and which can be absorbed into life. That discernment is itself an acquired skill.

Here is a non neutral take. We are too quick to fetishise public displays of accountability while ignoring quieter forms of competence. Video apologies are cheap. Quiet corrections cost time. If you value durable repair you might start paying attention to the less visible aftereffects of error management because that is where long term learning actually happens.

How this changes our conversations about age

Recognising how older generations respond to mistakes should change how institutions design feedback systems and how families allocate forgiveness. It is not about excusing stubbornness or elevating any age group. It is about being honest about the different economies of attention that shape behaviour. Organisations that insist on public mea culpas for every misstep will drive experienced people away. They will also miss real repairs happening off stage.

I will not pretend to resolve all the tensions here. Some actions require transparency. Some require discretion. What matters is matching the response to the moral and practical scale of the mistake rather than defaulting to spectacle.

Conclusion

Older generations do not respond to mistakes in a single predictable way. They filter prioritise correct quietly and sometimes stubbornly hold to familiar modes. That combination produces repair that is practical often effective and sometimes maddeningly opaque. If you want to learn from a lifetime watch what people do after the public moment has passed. That is where the actual change often lives.

Summary table

| Pattern | Typical older generation response | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Filtering | Selective engagement to limit harm | Preserves relationships and focuses resources |

| Correction focus | Prioritises factual updating and stability | Leads to durable learning not just performance |

| Regret calibration | Targeted regret used as teacher | Reduces rumination and guides change |

| Discretion | Chooses silence when public reveal would harm | Can prevent needless escalation |

| Structural blind spots | Habit can resist necessary change | Requires systems that welcome adaptation |

FAQ

Do older people admit mistakes less often than younger people

Not necessarily. Admission looks different depending on context. Older people may avoid public confession yet still take responsibility in practical ways. Studies show they can be better at correcting factual errors and at focusing attention where it will prevent recurrence. The public frequency of admission is not the best metric of accountability.

Is silence after an error the same as avoidance

Silence is sometimes avoidance and sometimes strategic restraint. The difference depends on whether harm is being mitigated and whether meaningful repair is occurring off stage. Evaluate the downstream actions rather than the initial lack of theatrical apology.

Can experience make someone less flexible

Yes. Experience yields pattern recognition but sometimes also entrenched habits. The remedy is an environment that values adaptation and provides clear feedback loops. Older people often respond well when invited into iterative improvement rather than shamed into change.

How should organisations respond to mistakes by senior staff

Match the response to scale and harm. Require transparency when public trust is at stake. Allow discretion and support when the priority is correction and continuity. Forcing public spectacle can discourage experienced staff from staying or from addressing problems thoroughly.

What can families learn from this about everyday apologies

Look for actions not performances. Repair in a family often happens in small acts over time. Prioritise consistency and concrete restitution rather than public declarations alone. That is where relationships are rebuilt.