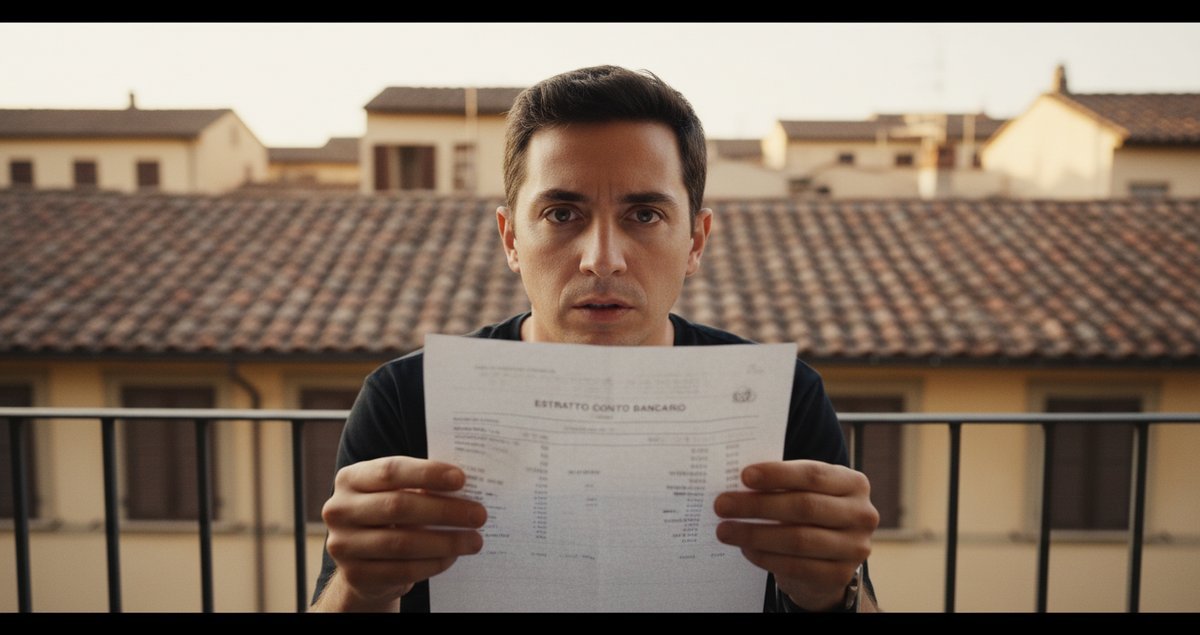

I had this smug calm about my money. It was the kind of calm that feels like a soft coat on a drizzly day. I checked accounts occasionally. I paid the mortgage. I bumped up retirement contributions. I told myself the small things were just that small. Then one evening I found a line on a bank statement that read like a whisper and not a shout. It was a recurring charge that added up to 1,100 euro a year. By the time I did the math it was no longer background noise.

How complacency hides a cost

Complacency is a skilled thief. It takes the form of forgetfulness but it is not innocent. In my case the charge had been on autopilot for more than a year. I had signed up and forgotten. Or rather my brain had chosen to forget it because it was small enough to live in the margins of attention. A familiar pattern emerged. I noticed the charge only when something else nudged me to look. The pattern is common and boring and also quietly devastating to budgets over time.

Not a story about frugality. A story about attention.

I am not lecturing about cutting expenses for the moral thrill of austerity. This is about how attention is currency. When attention disperses, money flows without negotiation. The 1,100 euro a year expense was not a villain in a cloak. It was a polite recurring payment with a name and a small monthly line that never asked for permission twice. It taught me something about how we let rules of least resistance govern our money.

The moment that feels both petty and important

There was an odd pleasure in discovering the number. It felt petty to be rattled by something so specific. And yet the arithmetic was stubborn. Add up a dozen tiny autopayments and you have the price of a plane ticket. You have a chunk of a yearly tax bill. You have the power to shift priorities if you actually see the numbers. Seeing them changed me. Not immediately in some cinematic sweeping simplification. More like a small gear in my mental machinery clicked and I began to audit the slow leaks.

“System 1 continuously generates suggestions for System 2: impressions, intuitions, intentions, and feelings. If endorsed by System 2, impressions and intuitions turn into beliefs, and impulses turn into voluntary actions.” Daniel Kahneman Nobel laureate and professor emeritus Princeton University.

Kahneman reminds us that most of our decisions run on autopilot. That autopilot is efficient for making coffee but not always for guarding your bank balance. Once I framed the recurring charge as a psychological phenomenon rather than a moral failing I felt less shame and more curiosity. Curiosity is a better habit to build than guilt.

Why we tolerate small recurring charges

There are several structural reasons. One is timing. Monthly payments are easier to swallow than annual ones. Another is friction. It is harder to cancel a service when the company designs the process to be slightly obscure. And there is a behavioral reason that matters to me personally: inertia tastes like security. It is safer to let things continue than to interrogate them, until you discover a yearly total that you did not authorize in your head.

A tactical confession

I did not slice through every recurring cost in a single afternoon. I started by asking three questions about each charge. What is the exact benefit I receive. When did I last use it. Could the value be replaced cheaper or for free. Those questions are annoyingly simple but they force System 2 to show up. You do not have to be ruthless to be sensible. You only have to be willing to look straight at the numbers and feel slightly inconvenienced.

Small rituals that actually work

I now run a ritual at the end of each quarter. Not an elaborate financial deep dive. Just twenty minutes with a cup of coffee and the account statements open. I trace recurring charges and write them on a single sheet. That sheet becomes a conversation starter with my partner. The ritual is imperfect. Sometimes I skip it. Often it reveals things I did not expect. The number 1,100 euro became a story we could change rather than a silent drain that normalized itself.

Why the standard advice fails

There is a tide of articles that say audit subscriptions and cancel. They are true and they miss the point. Canceling is not the hard part for most people. The hard part is cultivating the attention to notice the cost and then negotiating the small emotional loss we feel when we give up a convenience. The best advice I can give is not a checklist. It is a practice of noticing. Learn to treat your monthly statements as narratives rather than as wallpaper.

When a small thing reveals a larger habit

Finding that 1,100 euro a year expense made me look at other habits. How often was I paying for value I did not use? How often did I buy ease because the future version of me seemed like a kindly but passive character? The answer was that I was outsourcing decisions to a future self who was vague about priorities. The fix is not heroic. It is communal. Discuss money in real sentences. Make it shareable. That small social friction prevents autopay from becoming automatic permission to waste.

What I changed and what I refused to change

I canceled a few services that were mostly symbolic. I consolidated accounts. I negotiated one provider down to a lower tier. I refused to make every choice a battle. There are conveniences I value and the money spent on them is not waste. The change was more about intention than thrift. I wanted to know why we were spending money and whether those reasons still held.

Lessons that stick

The lesson was not that small charges are evil but that small charges require a small practice. The calm I prized was real but it had been partly purchased with inattention. Attention is not free but it is cheaper than regret. I cannot tell you this will fix everything. It did not. But it changed the narratives running in my head about what is worth keeping and what is worth letting go.

Final thought

If you suspect you have a hidden annual bill catch it early. If you do not suspect anything the absence of worry is not proof of financial health. It is only proof of a particular state of mind. And that state of mind can be nudged into a slightly more deliberate posture with habits that take minutes not days.

Summary table

| Issue | What I did | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Hidden recurring charge 1,100 euro a year | Found it by auditing statements and canceled or reduced services | Recovered annual spending and redirected funds to priorities |

| Complacency | Quarterly 20 minute ritual with statements | Restored attention and created social accountability |

| Decision inertia | Three question filter for each service | Forces System 2 engagement and clearer choices |

| Emotional resistance to canceling | Reframed as experiment not deprivation | Makes change sustainable without theatrical cuts |

FAQ

How can I find small recurring charges without spending hours?

Start with a single sheet of paper and list every recurring line you can find in a bank account for the last three months. You do not need to evaluate everything in that moment. Circle the items you do not immediately recognize and set a timer for twenty minutes to investigate. The point is to make it predictable and doable so you do not procrastinate. If you use a partner or friend turn it into a brief shared ritual so accountability reduces friction.

Is it worth negotiating with providers or just cancel?

Both options are valid depending on the value you get. Negotiation can be effective because companies often retain customers at lower rates. But negotiation requires effort and sometimes the time cost outweighs the savings. A practical approach is to ask for the retention offer once and compare it to cancellation plus a short cooling off period before deciding. The point is to treat the choice as a transaction rather than an emotional reflex.

Will checking statements more often make me anxious?

It can for some people. If you notice anxiety dial it down to a quarterly ritual instead of monthly. The goal is not obsessive micromanagement. The goal is to build a reliable habit of attention that prevents large unnoticed drains. If the practice increases anxiety then change the cadence or the environment in which you do it so it feels less like policing and more like a regular check in.

How do I decide which conveniences to keep?

Ask whether the convenience replaces a meaningful time or quality benefit. If a service saves you several hours a month and those hours are used for valuable activities then it might be worth the cost. If the convenience mostly avoids minor friction that you can tolerate once or twice then it is a candidate for cancellation. Decisions do not have to be permanent. Treat many of them as experiments that you can reverse if they do not work.

Will small fixes scale to major savings?

Sometimes. Often small fixes free up attention and funds that cascade into larger decisions you can finally make. Recovering 1,100 euro a year in my case did not single handedly change retirement outcomes but it rewired my relationship to daily decisions. That marginal gain often compounds into better choices that are easier to sustain because they are anchored in attention rather than in willpower alone.