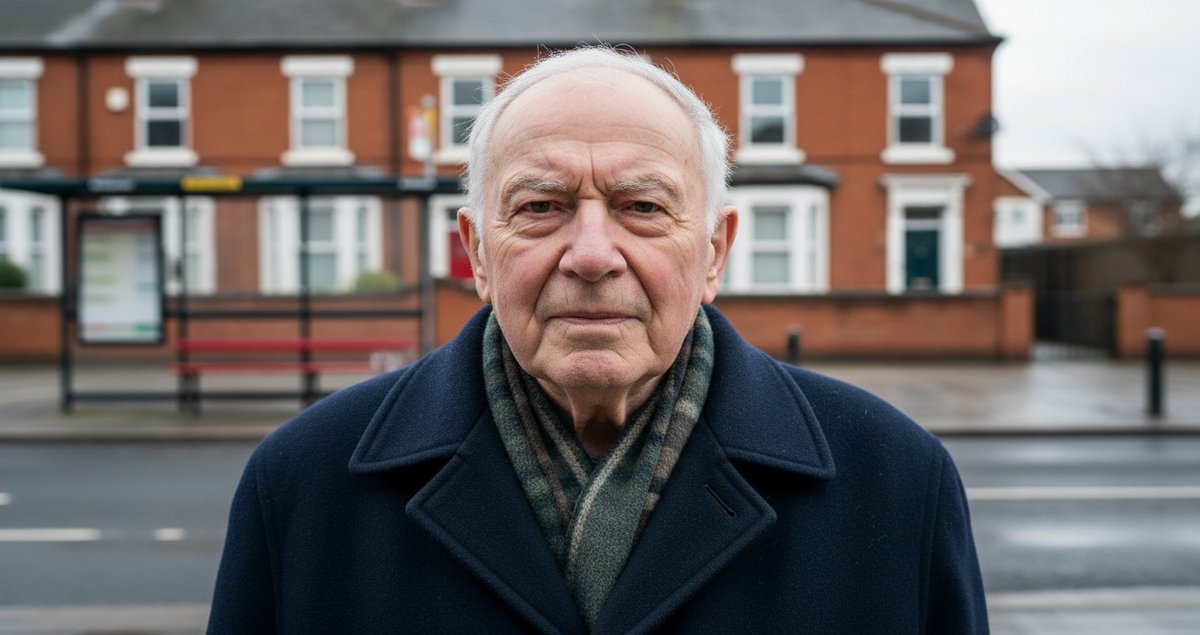

There is a small, slightly disarming ritual many of us have noticed but rarely name. An older neighbour leans forward, fixes you with a steady gaze and speaks as if they are sliding a coin of their attention into your palm. You feel it immediately. The conversation seems cleaner. The other person seems worth listening to. Call it intuition if you like. Call it social muscle memory. I think it is also a deliberate, learned tool that older people use to shape how they are treated.

That look is not accidental

We live in an era of distracted attention where eyes flit toward screens and polite glances thin into brisk nods. So when an older person holds eye contact it registers like a small act of defiance against the scatter of modern life. It reads as seriousness, as gravity. I have watched this happen in waiting rooms and on buses. The younger person will often soften, will half turn their body, will speak slower. Respect, in practice, is as much an exchange of attention as it is a set of words.

Older eyes as social punctuation

Eye contact is a social punctuation mark. In conversations where people rush, an older speaker will use steady eyes to signal pause and demand an audience. It is a technique that stops the scroll of distraction. It can work like punctuation because we are wired to respond to gaze in ways we barely notice. Long before we had screens to look at, our brains learned that being looked at was a cue to pay attention. That ancient wiring still matters now.

Science and a memory of faces

This is not just folklore. Decades of social psychology research show that direct gaze affects how we judge others. Michael Argyle and his colleagues described gaze as linked to affiliation and the regulation of intimacy and conversational flow. Their work explained how eye contact signals our emotional stance and influences closeness. When an older person fixes you with a steady look, they are using a channel that can alter the conversation at the level of attention mechanics.

There are also studies showing that direct gaze increases perceived likeability and social preference across age groups. The detail that interests me is how older adults often preserve the social benefit of gaze even as other cognitive effects of ageing shift. That preservation is itself a resource. The look becomes a kind of social capital older people carry.

Expert voice

Rosalinda Randall etiquette expert says Making and maintaining eye contact is the most fundamental way to show respect and to acknowledge another person. A connection can help reduce self protectiveness allowing for a more positive start. Rosalinda Randall Parade.

Why older people use it and what it buys them

From observation and from conversations with older friends I can point to a few reasons. For some it is habit. They were raised in eras when face to face manners mattered and eye contact was taught as a basic courtesy. For others it is strategy. If you have been dismissed or overlooked you learn to correct course. People who felt ignored as younger adults often become more direct. You will find older activists and retired teachers who will intentionally hold your gaze until you answer, because the gaze is the minimal force necessary to reclaim attention without raising your voice.

There is also truth-telling in this practice. When someone looks you in the eye they are making less room for performance. You see micro shifts in expression, a quick tightening of the mouth, a flash of humour. That transparency can make the speaker feel more credible. It is a kind of conversational honesty that some of us have allowed to atrophy. Older speakers sometimes know that and use the look to hush the noise.

Not always comfortable

Let me be blunt. Eye contact can be oddly confrontational. It can feel like interrogation if overused. Not everyone can reciprocate easily. Neurodivergent people and people with certain trauma histories may find direct gaze draining or triggering. But the persistence of the behaviour among older people suggests it is valued enough that they will accept the occasional awkwardness if it produces what they want which is attention and respect.

How eye contact reshapes our behaviour

The effect is often subtle. Imagine two short exchanges. In one the speaker looks down frequently and speaks in a clipped tone. In the other the speaker looks up and stays steady. In the second exchange the listener tends to reply with fuller sentences. They slow down. The listener is more likely to make room in the conversation. This is not magic. It is a calibrated signal. It says I am present. It asks for you to match presence.

To some degree this is cultural choreography. In a crowded London cafe a deliberate gaze will nudge people into a different register. In a quiet village hall the same gaze will be taken as an instruction to treat the speaker seriously. Whether we like it or not our responses remain partly automated by this choreography.

What we underestimate

We often underestimate that older communicators are teaching us. Each time an older person holds our gaze they are modeling different social expectations. They are reminding us that conversation once had a tempo and an attention economy that rewarded presence over distraction. That reminder can be mildly irritating to younger people who prefer movements and fragments. But it can also be restorative if we take it as a nudge rather than a rebuke.

Practical consequences and a bit of moral impatience

Here is where I get a little impatient. Society claims to value elders while systemically making them less visible. We talk about dignity and then program everything for speed. So when an older person takes the time to meet your eyes they are often doing double work. They are insisting on visibility and they are asking to be heard. Not returning that attention is a small cruelty wrapped in convenience. I do not demand theatrical reverence but I do ask for awareness. A returned gaze is cheap and often does as much good as a kind remark.

Sometimes I think about the consequences for politics and public life. Leaders who learn to hold the gaze of older voters know how to signal seriousness. Campaigns and institutions that ignore this lose not only votes but the weight of moral authority that comes with listening to lived experience. Eye contact is a small therapy for public life. It repairs the worn edges of civic talk.

Open ended ending

This is where I stop trying to tidy the matter. The look may be affectionate, tactical, stubborn, generous, performative or sincere. All those things can coexist. The older person who looks you in the eye while speaking is not only making a social move. They are making a claim about how conversation should be done. You get to answer that claim however you wish. Often you will answer without thinking. That reflex is worth noticing, and sometimes changing.

Respect is not only a noun to be granted. It is a movement to be mirrored. If older people are the ones reminding us to do the mirroring then we should pay attention. Not because of age alone but because their gaze still often works.

| Key Idea | What it means |

|---|---|

| Intentional gaze | Older people often use steady eye contact as a tool to secure attention and shape conversation. |

| Psychological effect | Direct gaze increases perceived likeability and encourages listeners to slow down and engage. |

| Cultural habit | Generational manners and learned strategies both explain the prevalence of the behaviour. |

| Limits | Eye contact can be uncomfortable for some and can feel confrontational if overused. |

| Social cost | Failing to return attention to elders is a small everyday discourtesy with cumulative effects. |

FAQ

Why do older people seem to use more eye contact than younger people?

Many older people grew up with conversational norms that prized sustained attention and clear face to face signals. Over time those norms become habits. In addition some older adults choose to use eye contact strategically to ensure they are heard in settings that may otherwise dismiss them. This is both cultural memory and a tactical adjustment to social environments that prize youth and speed.

Is steady eye contact always a sign of respect?

No. Steady eye contact can signal respect but it can also be used to assert dominance or to interrogate. Context is crucial. Tone of voice posture and the surrounding interaction all clarify whether eye contact functions as politeness or pressure. Often it speaks as part of a whole ensemble of signals rather than as a standalone proof.

How should I respond if I find sustained eye contact uncomfortable?

It is fine to manage your own comfort. You can acknowledge the speaker with a slight nod a verbal cue or by angling your body in a genuinely engaged way that does not require prolonged gaze. Being honest when appropriate is also useful. Many people accept the space for different social styles once it is named without making the exchange into a moral judgement.

Can learning to use eye contact change how people treat me?

Yes it can influence first impressions and the flow of conversation. Using direct but not oppressive eye contact can increase perceived trustworthiness and encourage more measured responses from listeners. That said it is only one part of communication and should be balanced with listening and clear speech.

Is there research that supports the social power of gaze?

Yes. Classic social psychology work describes gaze as linked to affiliation intimacy and conversational regulation. Contemporary studies continue to show that direct gaze affects judgments of likeability and attention across age groups. These findings underscore how small nonverbal acts can shift social dynamics.