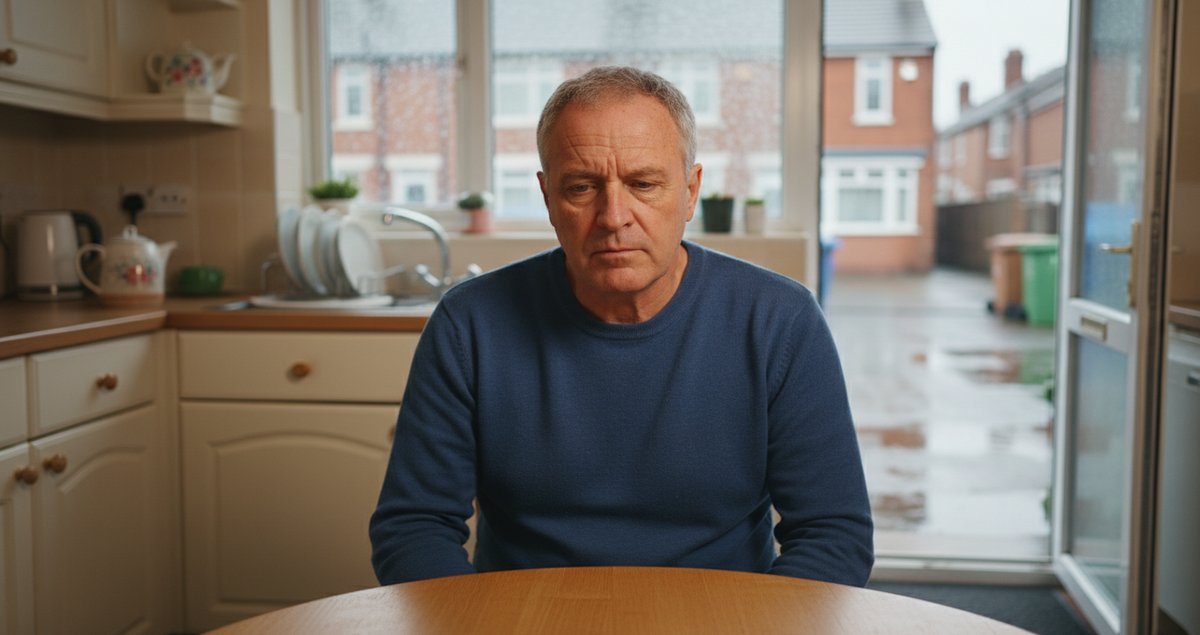

There is a stubborn charm about how people who grew up in the 1970s handled their inner weather. It is not that they were less emotional. Far from it. Many of them were loud in feeling and quick in judgment. The difference lies in an everyday habit of separating what was happening inside the body from what could be demonstrated outside it. That separation made room for debate, repair, grudging humility, and sometimes very human stubbornness. This is the story of that habit and why, in our current rush to collapse sensation into truth, we have something important to learn.

How a generation learned to map feelings without collapsing into them

People from the 70s experienced big cultural shifts public and private. Those shifts taught them to notice unrest and to name it. They learned to label anger, to sit with grief, and to treat suspicion as a thing to check against evidence. This is not romanticising a decade. It is noticing a pattern: the social scripts of that era often demanded discussion after outrage not immediate certainty. That habit did not make them immune to bias. It made them more practiced at asking whether a swelling in the chest meant a fact or an alarm signal needing investigation.

Not ice cold logic but practical distance

There is a common misconception that distinguishing feelings from facts is an intellectual trick practiced by ivory tower types. In the 70s it was practical. People worked in offices and factories. They argued at kitchen tables. They wrote letters. The processes of making decisions in groups required a shared reality. It was easier to isolate feelings as data about internal states rather than treat them as verdicts about the world. That stance preserved actionability. You could be furious and still test the timeline. You could be heartbroken and still check the bank ledger. This is simple and, in its way, durable.

Why we stopped doing it as reliably

Fast forward to now and the pipes that carried emotion into public life are wider and louder. Social platforms feed immediate resonance and reward the leap from feeling to claim. The old pause—the small social contract that a feeling can be spoken but must be verified—has eroded. In its place we have a steady pressure to convert affect into fact in real time. This is not a neutral change. It reshapes accountability, slows genuine curiosity, and rewards certainty over nuance.

The technology of conviction

There is an architecture to how we now build reality. Algorithms prioritise engagement which often correlates with emotional intensity. The result is a feedback loop where feeling becomes the fastest route to being heard. For people raised in the 70s this pace felt unnatural. For many of their children it feels normal. The consequence is predictable: quicker judgments, louder reputations, and a shriller politics of emotion.

What the research and clinicians say

When people are in distress or engage in unhelpful behavior some of their thoughts are distorted or unhelpful and when they learn to identify evaluate and respond to their thinking they generally have an improved reaction.

Judith S. Beck PhD President Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy.

That is not a cultural slogan it is clinical ground beneath many modern therapies. The distinction between feeling and fact sits at the heart of cognitive models of mind. Clinical practice shows us emotion is essential and informative but not coterminous with truth. The 70s generation used such a distinction not because they were less passionate but because their social environments demanded it.

A personal note: why I still trust a measured gut

I was raised on stories about my father reading the newspaper twice before he spoke about politics at dinner. He did not lack for opinion. He simply believed that something burning inside him did not automatically equal a reliable history. That small habit of verification carried him through several noisy periods where he would otherwise have been swept by rumor. I keep thinking about that in the age of instant outrage. There is a moral quality to the habit of checking your feeling against the world. It protects other people and, paradoxically, your own dignity.

The social dividend

When personal affect is held as provisional it enables repair. Apologies become possible because the original claim can be revisited without collapsing identity. That is not merely a sentimental idea. It changes conflict dynamics. If you start from the premise that your feeling is a hypothesis rather than a verdict you can enter an argument with less need to be right and more capacity to be persuasive. Societies that sustain such habits have an easier time working with disagreement and reconciling after friction.

Three misunderstandings that keep the feeling equals fact myth alive

First misunderstanding is rhetorical: feelings are treated as more persuasive than evidence because the former are immediate. Second is psychological: intense emotion narrows cognitive bandwidth so people naturally cling to impressions. Third is technological: platforms reward the shape of certainty not the contour of doubt. If you unpick any public argument today you will find at least two of these forces at play.

It is also worth saying plainly that insisting feelings are separate from facts is not an invitation to dismiss feelings. It is a plea to treat feelings as data with meaning, not as the whole truth. That nuance has been lost in many public debates and personal rows where one side says feelings matter and the other side responds as if feelings were irrelevant. Both errors are easy to make and expensive to live with.

Small practices that echo the 70s without faking them

I am opinionated here. I think the modern world would do well to borrow some modest rituals from that era. Not for nostalgia but for function. Try saying aloud I feel X right now then ask what observable facts you can list that support this. Pause before tagging someone in a public post. Offer your certainty as a provisional claim. These are not panaceas but they reintroduce a space between somatic alarm and public claim.

What we might lose if we do nothing

If we continue to compress inner life into shared truth claims unchecked we diminish the capacity for nuance. Public institutions will feel shallower. Relationships will calcify into positions. The 70s habit of treating feeling like evidence of a condition rather than evidence of reality may sound quaint but its absence is obvious in the brittle moral certainties that mark many debates today.

Final thought

There is no perfect generation. The 70s were messy and often unjust. Yet their practical approach to separating feelings and facts left a legacy that still works. It allowed arguments to be arguments rather than show trials. It offered an uncertain but useful approach to living: feel hard then verify. Perhaps that is worth reviving not as a doctrine but as a small social skill.

| Key idea | What it does | How to try it |

|---|---|---|

| Separate feeling from claim | Prevents immediate conflation of emotion with objective truth | Phrase feelings as hypotheses then look for evidence |

| Hold affect as information | Respects emotion while avoiding verdicts | Ask what the feeling signals and what it does not |

| Delay public judgment | Reduces reputational harm and allows repair | Wait before posting reactively and invite corroboration |

FAQ

Is it wrong to treat a feeling as evidence in personal relationships?

Not necessarily. Feelings are always evidence of internal states and deserve to be heard. The problem arises when they are presented as verifiable facts about another person without supporting observation. In close relationships it is productive to say I feel this and then ask for what happened rather than issuing a final judgment. That language invites conversation and reduces the chance of escalation.

Did people in the 70s never confuse feelings with facts?

No. People from every era make the same mistakes. The point is not perfection but habit. The 70s culture often had more social rituals that encouraged checking a feeling against a timeline and other witnesses. That made mistaken convictions less likely to become public immovable truths.

Can modern therapy help with emotional reasoning?

Yes therapy, particularly modes derived from cognitive principles, teaches people to notice emotional reasoning and to test assumptions. Therapists encourage the practice of listing evidence for and against a belief triggered by emotion. Clinical work does not erase feeling it helps people use feelings constructively.

How do we teach younger people to separate feelings and facts?

Teach curiosity. Model the habit of pausing. Use language that frames feelings as provisional. Encourage practices that require checking observable facts before making broad claims. Over time these small rituals can create cultural habits that mimic the practical verification tendencies we saw in previous decades without asking anyone to be unemotional.