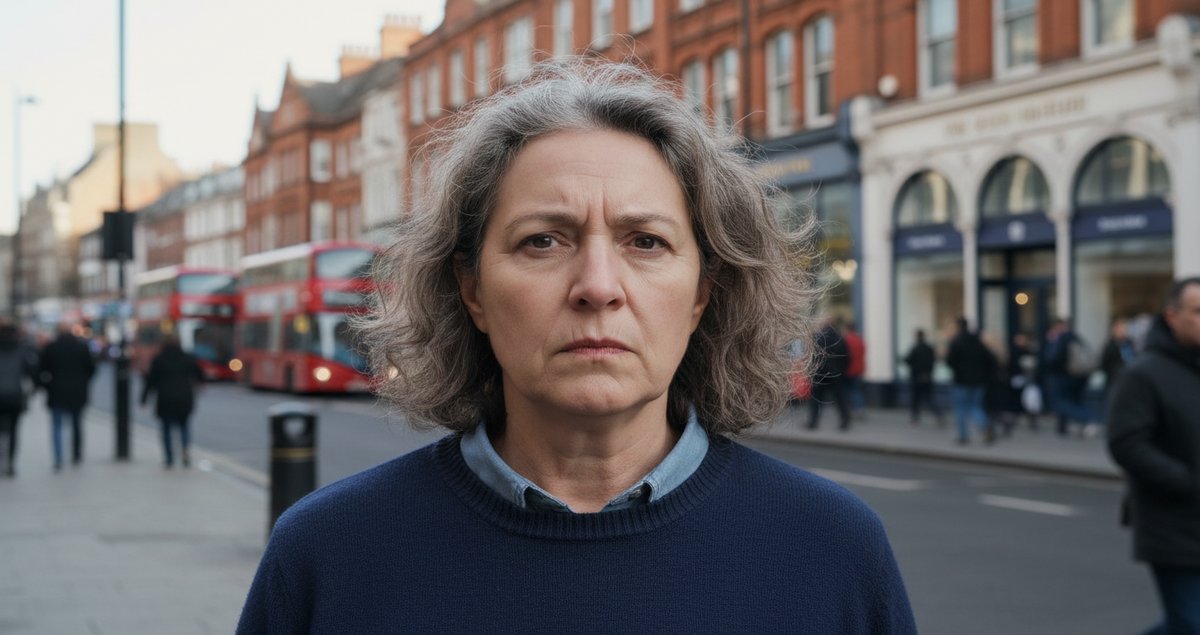

There is a strange kind of hindsight that arrives with age. People born in the 1960s have been dismissed as nostalgic or nagging when they tried to point out cultural tensions we now live inside. They did not always speak in tidy manifestos. Their warnings came as impatience at work meetings, as a refusal to join the first wave of corporate buzzwords, as odd little lifestyle choices that looked eccentric at the time and sensible now.

Not prophecy but pattern

Here is what they were actually doing. They were cataloguing patterns. They noticed the way attention shifted from conversation to commodified distraction. They had a front row seat for the shift from affordance to addiction. They saw environmental cost listed as collateral in product launches. They watched institutions outsource responsibility to technologies and to markets and called that arrangement fragile. That is not mystical foresight. It is observational acuity combined with lived discomfort.

Why those observations mattered then and matter more now

When someone born in the 60s complained about the new normal they often felt unheard because the cultural grammar of the moment prized novelty and scale. The loudest voices celebrated disruption. But disruption for its own sake is not the same thing as human flourishing. Psychology now gives us tools to translate that early unease into measurable concepts — attention economy, social capital, cognitive load, intergenerational stress — and in doing so it vindicates many of the older complaints without turning them into moral panic.

The attention toll: not a tech problem alone

It is easy to point a finger at devices. The deeper point people born in the 60s were making was social and structural. They noticed the thinning of rituals that stitched communities together. The gap was not created by a handset; it was widened when workplaces and schools rewarded constant responsiveness and when leisure became a place to consume a feed instead of to repair relationships. This is subtle. You can have abundant connectivity and still be socially impoverished. The generation that grew up before phones were personal saw the difference more clearly because the absence of omnipresent notification made the change legible.

Every time you check your phone in company what you gain is a hit of stimulation a neurochemical shot and what you lose is what a friend teacher parent or lover just said meant felt. Sherry Turkle Professor of Social Studies of Science and Technology Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Turkle is not delivering a sermon. She is naming an exchange rate of attention that the market does not account for. The people born in the 60s were pointing at those losses long before studies measured them. They felt them as irritations and as relational failure.

On work and worth

Another recurring warning was about the shifting contract between work and self. Those born in the 60s remember workplaces where identity was not wholly defined by a job title. They noticed as organizations flattened hierarchies on paper but not in power. They observed the elevation of metrics over judgment and the growing appetite for optimized human time. These were not old fashioned yearnings for stability. They were critiques of a system that started to value speed and scale over actual care.

Psychology helps translate the intuition

Research on burnout attention fragmentation and the psychology of decision fatigue shows why their unease mattered. The human brain was not designed for relentless context switching. When people born in the 60s warned about always being ‘on’ they were registering an early signal of a cognitive mismatch that would become visible at scale decades later.

Consumerism and the ecological argument

Some warnings had a material target. There were cautionary voices about the environmental cost of throwaway culture. Those born in the 60s lived through visible environmental decline and the birth of consumer abundance. They were impatient with marketing promises and with the assumption that convenience had no price. Psychology now explains why we discount long term harms: humans are wired to prioritise immediate rewards. That cognitive tendency is exploitable. The older generation understood the exploitation before behavioural economics named it.

Parenting and public life

People born in the 60s noticed a change in how societies raised attention and moral imagination in children. They were not simply nostalgic for playgrounds and unsupervised afternoons. They worried about the ways institutions subcontracted social development to screens and commodified extracurriculars. The criticism was often brusque and sometimes unhelpful. Still there is an underlying truth: the scaffolding that supports emerging minds has been shifting into spaces designed by engineers rather than by communities.

So iGen is the generation born 1995 and later they are the first generation to spend their entire adolescence with smartphones and thats had ripple effects across many areas of their lives Jean M Twenge Professor of Psychology San Diego State University.

Twenge studies cohorts but when she describes ripple effects she helps us connect two things the 60s cohort suspected and modern science confirms. The ripples are not deterministic but they are real enough to matter for policy and for how families choose to live.

A few places where their warnings were wrong or incomplete

This is not a simple triumph of vintage wisdom. Some of the 60s era critiques underestimated adaptability. People adapt to new norms and sometimes thrive in arrangements older critics assumed would hollow them out. They also sometimes romanticised an earlier public life that was less inclusive. It is important we read these warnings with nuance. They deserve to be interrogated not idolised.

What psychology still cannot decide

Psychology has illuminated mechanisms but not resolved the normative question of what we should value in a good life. Some changes are irreversible. New forms of intimacy have appeared that older generations did not predict at all. The 60s cohort warned about erosion but not about new possibilities that would arise alongside costs. We must carry both their caution and our curiosity.

Three practical impulses worth stealing from that generation

First reclaim a few minutes of unstructured attention in public life and treat them as nonnegotiable. Second design institutions that protect the slow time required for judgment. Third refuse the binary that pits progress against preservation. The appeal of those born in the 60s was rarely anti modernity. It was against a kind of haste that sacrifices the human for novelty.

Final imperfect verdict

People born in the 60s did not possess prophecy. They had an experiential lens that made certain hazards legible earlier than they were legible to others. Psychology has now placed labels and models on their intuitions which helps us act with more clarity. But the translation from insight to policy and from research to humane design is messy. Some of their warnings were scapegoated and some were prophetic. The job now is selective listening.

Summary Table

| Warning | What it maps to in psychology | Actionable idea |

|---|---|---|

| Attention loss | Fragmentation and reward driven checking | Protect device free rituals daily |

| Work replaces life | Burnout and identity fusion with job | Institutional limits on always being on |

| Environmental cost | Hyperbolic discounting and systemic externalities | Policy that taxes convenience that harms ecosystems |

| Children outsourced | Socialisation moved to screens | Invest in local community programs |

FAQ

Were the warnings from people born in the 60s mostly about technology?

Not exclusively. Technology is the most visible amplifier of the issues they named but many complaints were social and institutional. They warned about the way economic incentives and cultural values were realigning priorities toward growth and speed at the expense of conversation and repair. Technology is simply the medium that accelerated those realignments.

Is psychology saying they were right about everything?

No. Psychology gives us mechanisms that confirm certain risks are real such as attention fragmentation or decision fatigue. But it does not grant moral authority. Some predictions were overstated and some critics overlooked adaptive capacities in people and communities. Use psychology as a tool to evaluate claims rather than as final judgment.

How should we treat their advice now?

Treat it as a repository of experiments. Many people born in the 60s tried small countercultural experiments that now look like resilience practices. We can borrow the useful elements such as deliberate slow time and stronger local ties while discarding reactionary or exclusionary impulses. The best advice is to test practices in your life and in your local institutions and respond to the evidence you find.

Are there social harms that psychology has missed?

Psychology is still catching up on long term systemic harms because much of the research uses short term measures and convenience samples. The interplay between capitalism social media and inequality creates emergent effects that are hard to measure in neat lab studies. That gap is where the lived knowledge of older cohorts still matters most.

Can we respect their warnings without becoming nostalgic?

Yes. Respecting the warnings means extracting practical practices and structural insights and refusing the false choice between modernity and preservation. Nostalgia is a flavor that can obscure judgment. The useful stance is pragmatic respect mixed with healthy skepticism.

What is one small habit to start with?

Begin with one daily fifteen minute period where devices are set aside and you practice undirected attention. Do this in company when possible and treat it as an experiment. See what changes in your sense of patience clarity and conversation over a month. It is small and it highlights the hypothesis the 60s cohort have been pressing for decades.

Some warnings were blunt and uncomfortable. Many were right. The rest remain provocations. That is not failure. It is how culture learns.