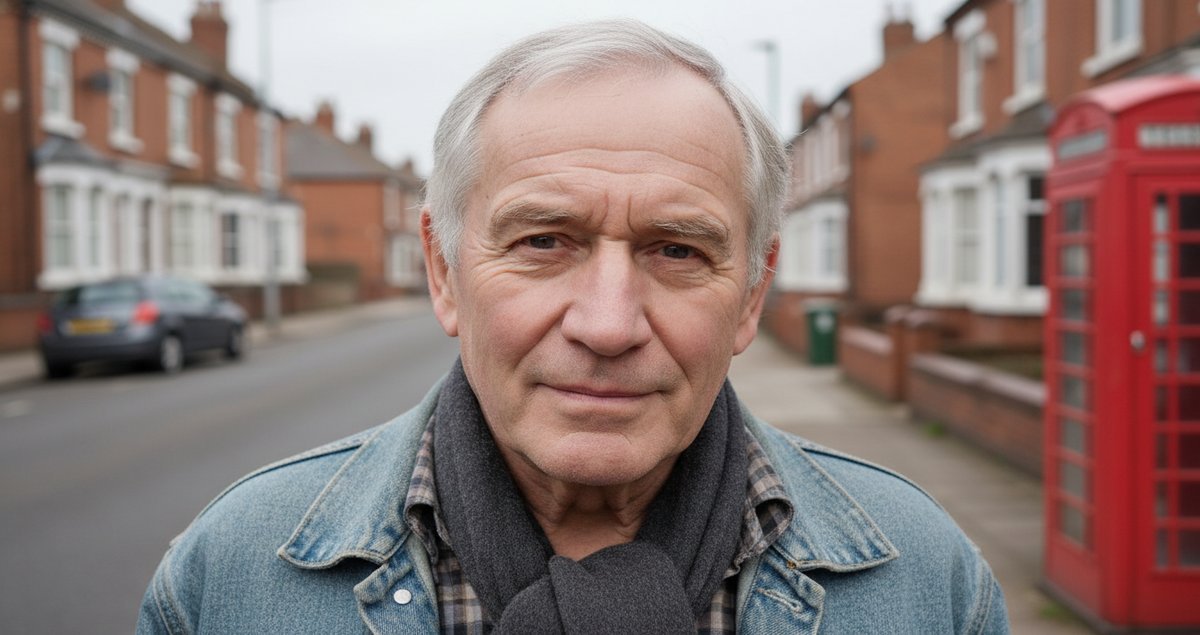

There is a quiet stubbornness to people who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s. It is not swagger exactly. It is not the loud confidence of a headline generation. Instead it feels like a steady coil of conviction that has been tightened by decades of small practical truths. They rarely talk about fearing age the way younger cohorts do. They may grumble about knees or eyesight. They may make jokes that mask a shiver. But outright terror about getting older is uncommon. That difference is not just nostalgia. It is learned habit and cultural wiring and a particular mix of social history that still matters today.

What they learned as ordinary survival

People raised in the 1960s and 1970s grew up with an economy and a pace that demanded resourcefulness. They were taught to mend rather than toss. They spent hours waiting on the phone for a call rather than refreshing a feed. Those are small details that create a larger temperament. The temperament looks like less reactivity to change and more tolerance for slow disappointment. That shows up in middle age as a quieter acceptance of bodily decline and an ability to keep meaning intact even when daily capacities change.

Distress tolerance as a generational muscle

There is an old psychological phrase called distress tolerance. For many in these cohorts it became practical rather than clinical. Being able to sit with discomfort without frantic remedies meant they grew older with fewer catastrophising episodes. They did not need every ache to be evidence of imminent collapse. A scraped knee as a child does not equal a crisis as a pensioner. That comparative scale matters and it reshapes response patterns across decades.

Community habits that age with you

Communities were more local and more porous then. Neighbours were actual neighbours not curated profiles. People loaned tools and time and advice. When your social safety net is woven from daily reciprocity rather than distant institutions you end up fearing isolation less. People who grew up with that kind of social architecture enter later life with a practical expectation: help will be messy but it will appear. That is not a guaranteed truth. It is a working hypothesis they have carried, and it alters how they imagine the future.

Collective memory trumps imagined catastrophe

There is a certain archive of lived experience that dampens hypothetical dread. Surviving a national crisis or navigating tumultuous social shifts in youth builds a catalogue of what does not destroy you. This is not bravado. It is a ledger of losses survived. That ledger is invoked quietly. It sits behind jokes and pragmatic choices. It makes the prospect of aging less a cliff and more a season that you have weathered before in smaller increments.

We are perhaps the most death denying generation in human history having grown up in surreal conditions of modernity. Our parents knew wars and depression. We saw the golden age of the American dream the last generation of Americans certain to do better than our parents in a world that seemed on an inexorable road to progress. Sheldon Solomon professor of psychology Skidmore College.

The quote is blunt and illuminating. It reminds us why some members of the same cohorts fear aging intensely. Some carry a paradox. Growing up amid expectation of continuous progress generates a different kind of upset when bodies fail. Yet speaking generally there is a pragmatism that wins out for many. The mindset is less about denial and more about prioritising control over what can be controlled and deferring melodrama about what cannot.

Work patterns and the freedom paradox

Employment life cycles were different. Many people had long arcs inside single industries or even single workplaces. There are two consequences here that tilt attitudes toward aging. First there is a slower timeline of identity formation. Without the constant churn of job hopping your sense of self is not habitually tied to novelty. Second there were often clearer rituals for rites of passage. That made transitions legible which in turn reduces panic during later transitions. Some will call this conservatism. Fair. But it also made room for a steadier attitude toward later life.

Not resisting decline but recalibrating ambitions

People from these decades often treat aging as a problem of recalibration rather than immediate tragedy. They narrow some ambitions and widen others. That sounds simple but it requires patience most cultures do not value. It also requires permission. Many of them gave themselves that permission long before it was fashionable to do so. They were survivors of an era that prized improvisation. That improvisational skill translates into less fear and more adaptation when years begin to rearrange priorities.

Why this is not romanticising and why exceptions matter

Let me be clear. Not everyone raised in the 1960s and 1970s inherits these traits. Class and race and gender and geography reshape outcomes. Structural insecurity does not vanish because someone learned to fix a bicycle. Loneliness and economic fragility are real and can make aging terrifying for many. When the story is told as a universal triumph it erases painful variation. My point is narrower. There are patterns shaped by that era that give some people a different relationship to later life and those patterns deserve attention not dismissal.

A late life ethic that is less performance driven

A surprising feature is how many in these cohorts refuse the performance script of later life. They decline the cult of perpetual optimisation that insists every grey hair must be fought. They adopt a less theatrical approach. It is not because they do not care about appearance. It is because they grasp a deeper arithmetic. Time invested in relationships and craft often yields more return than time spent on cosmetic illusions. That is a value judgement. I believe it is a sound one. You may disagree and that is part of the conversation.

Small acts that accumulate into a larger courage

There is a simple catalogue of small practices that add up. People who weathered rationing sensibilities or tighter finances earlier in life are less likely to panic at financial volatility later. Those who practiced delayed gratification by necessity internalised a different patience. Those who grew used to waiting for news or results learned to sit with uncertainty. These are not glamorous skills but they are powerful. They produce a typical calm that looks like courage to younger eyes.

Why younger people misread this calm

Younger observers sometimes interpret the calm of older people as complacency. That is a misread. The calm is often a product of many small refinements in living. It is less spectacular than anxiety but it is more durable. And it is contagious when it is modelled authentically. I have watched people in my life who grew more patient and less reactive simply by living with elders who treated aging as an ordinary extension of time.

Conclusion that leaves a question open

The case for why people raised in the 1960s and 1970s rarely fear getting older is not reducible to one cause. It is a composite of social habits lived practice and a set of adaptive responses that were learned when everyday life demanded them. It is also a moral and political position whether they mean it to be or not. Choosing to treat aging as a season rather than a catastrophe is an ethical stance toward the future. Whether that stance will be transmissible to younger cohorts who grew up with different scripts is still unresolved.

| Theme | What it produces |

|---|---|

| Distress tolerance | Less catastrophic thinking about bodily change |

| Local reciprocity | Lower fear of isolation and more practical social support |

| Work continuity | Smoother identity transitions into later life |

| Practical patience | Better recalibration of ambitions and priorities |

FAQ

Does this mean people from those decades never worry about getting older

No. Worry exists across generations. The claim is not absence of worry. It is a relative pattern. The difference lies in how worry is managed and how often it tips into panic. Structural factors like income and social support deeply condition that pattern.

Are these observations backed by science

There are psychological concepts and sociological studies that align with these observations such as distress tolerance and social capital research. What I offer is an interpretive synthesis that highlights lived practice rather than a single causal study. The patterns are visible in multiple qualitative and quantitative sources but they are not absolute laws.

Can younger generations learn these habits

Yes some practices are learnable. Patience the ability to repair or to rely on local networks can be cultivated. But these habits are also shaped by economic and social structures which have changed. Learning them without structural support is harder but not impossible.

Is this article advice on health or medical matters

This article reflects observations about attitudes and social patterns. It is not medical guidance. Decisions about health should be made with qualified professionals and personal circumstances in mind.

What is the biggest misconception about aging among these cohorts

The biggest misconception is to imagine their acceptance of aging is passive resignation. It is not. It is often an active choice to prioritise certain goods over a cultural obsession with perpetual youth.