When I first scrolled past the listing it felt like a prank. The photos were grainy phone shots of beige boxes stacked like ancient bricks under rafters. The title repeated itself in small type. The price tag read less than 100 euros each. The primary keyword 2,200 computers were stored in a barn for 23 years the owner sold them on eBay for less than 100 euros each is a long sentence but it is also the story. It is a headline that tries to hold both shock and a kind of quiet ruin in the same breath.

Not a treasure chest. Not quite junk either.

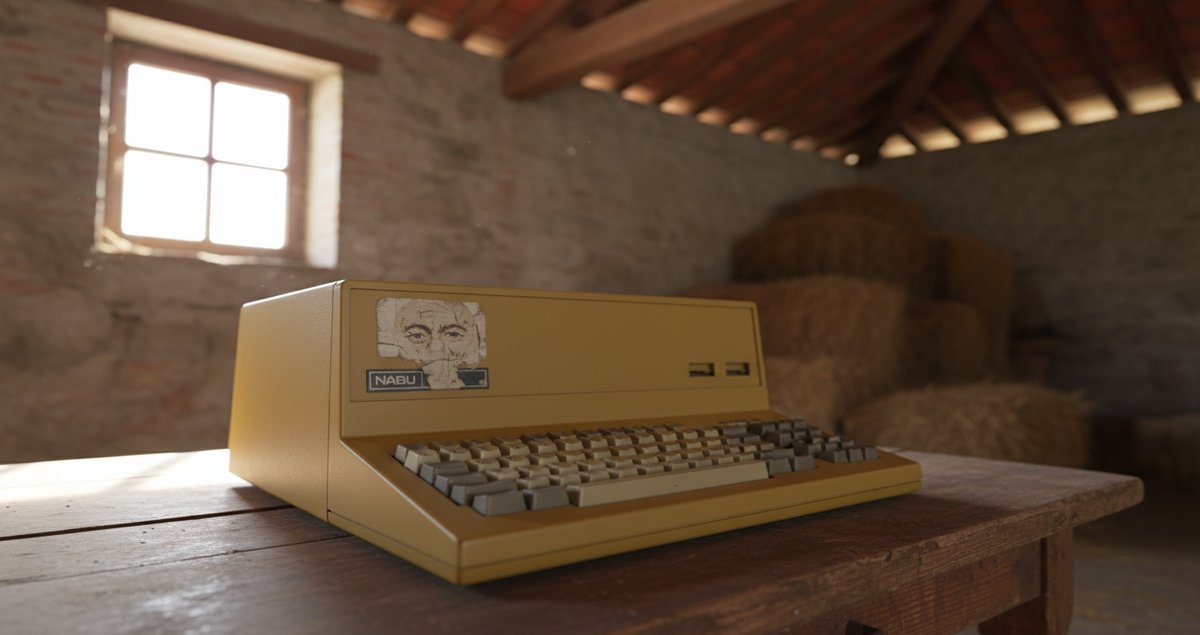

Let us be blunt. These were not mint sealed consoles destined for glossy museum vitrines. They were NABU machines from the early 1980s. Their architecture is foreign to most modern eyes. Their plastic had yellowed. Their packaging was an argument about how time eats materials. And yet when a retiree who had stored them in a Massachusetts barn began selling them on eBay the reaction was immediate and contradictory. Collectors rejoiced. Makers made plans. Landfill advocates sighed. Economists shrugged. The sequence of events exposed how value is assigned and reassigned by communities rather than by neat markets.

What the machines actually are.

NABU was an oddball dream of networked home computing delivered through cable television long before internet ubiquity. The devices required a headend and a cable adaptor to pull apps and games down to a home terminal. To the engineers who built them they were an experiment in distribution. To many buyers in 2023 and 2024 they became objects to resurrect and repurpose. The fact that 2,200 identical units sat in a barn for 23 years is almost a technical footnote. The surprising part is that the online market accepted them at a price below 100 euro each and treated them as meaningful at that level.

Why this pricing is not as silly as it looks.

There are three separate markets at play. One is the museum and conservation market where provenance, rarity, and condition drive the value higher. Another is the hobbyist reverse engineering market where cheap hardware is a raw material. The third is the electronics parts and recycling market. The barn find touched all three. Listing items cheaply on eBay is an invitation to a widely distributed discovery process. Some buyers wanted a curio. Others wanted parts or the thrill of making one work. The owner cleared decades of storage risk for what, on paper, looks like a modest return. In practice it is a redistribution of possibility.

“The NABU Network was an innovative attempt to radically reshape the principles of personal computer based public access to information and entertainment.” Zbigniew Stachniak Professor York University Computer Museum.

That quote matters because history lives in dusty corners.

York University Computer Museum has documented the NABU story and good curatorship means someone will take a handful of these machines and keep them running. But most of the 2,200 will not enter institutional collections. Most will be played with by people who want to learn how networks used to be stitched together. Some will be cannibalized for parts. A few will be photographed for an Instagram caption and then forgotten. I find that messy outcome honest. It respects that not every artifact should be preserved perfectly. Many deserve to be used imperfectly.

The barn as a lens on how we value technology.

There is a short cultural diagnosis here. When new technology arrives it is embedded in stories about progress and inevitability. When that era ends those stories fragment. We who live on the other side impose new narratives. Nostalgia can inflate value. Technical curiosity can do likewise but in a different direction. The eBay listings were a marketplace reflex. They let small bets be placed by many people rather than a museum curator making a single editorial decision. That distribution of risk and attention produces weird pricing outcomes. It also surfaces projects that we did not know we needed.

Personal observation: the emotional geometry of secondhand devices.

I watched forum threads where strangers consoled one another about the difficulty of getting these boxes to boot. There was an earnest delight in soldering and in coaxing life out of a machine that once expected a cable network. That delight is not justification for market value. But it explains the cultural hunger. These are toys for grown people who prefer the labor of repair to the ease of instant streaming. There is an ethical bend to it too. Buying an old computer instead of a new single use gadget slows the churn.

Who benefits and who loses.

The owner who needed the barn cleared benefits by de-risking property collapse and avoiding disposal costs. The buyer who scored a working piece of history benefits with a low entry point into a niche. The environment benefits slightly from a delay in immediate recycling and landfill. But museums and preservationists lose units that could have been curated meticulously. That tension is real and unsolvable in a single sweep. You cannot preserve everything. The eBay solution distributes the archive across thousands of small custodians. That distribution will produce both serendipity and waste.

Why this story is bigger than nostalgia.

Because it shows a pattern. Technology is rarely a straight line. It is a web of attempts some of which are later recognized as prescient. NABU anticipated distributed content delivery. It did so without the infrastructure or capital to scale. Two decades of storage turned a commercial failure into a historical resource. Selling those units cheaply on modern marketplaces is the closing of a loop where the future becomes the past and then becomes raw material for new futures. That circularity is underreported and underappreciated.

Open ended questions worth holding on to.

What happens to the private histories embedded in those machines. Who owns the software that used to stream through cable networks. Can communities of hobbyists keep a distributed archive alive. When is a market an adequate steward for heritage. These are not problems that have single tidy answers. They are collaborative frictions that demand multiple small experiments rather than one large preservation decree.

Final note.

The listing of 2,200 computers were stored in a barn for 23 years the owner sold them on eBay for less than 100 euros each is more than a headline. It is a vignette about how we negotiate value in an age where both hardware and meaning age quickly. The barn was a storage problem turned into a community event. The price was low on a per unit basis. The cultural return may be large and weird and not easily measured.

Summary Table

| Item | What to take away |

|---|---|

| Object | NABU home computers originally built for cable delivered content. |

| Context | Stored in a barn for 23 years then sold on eBay with many units listed under 100 euro each. |

| Markets involved | Museums collectors hobbyists parts recyclers general buyers. |

| Why price was low | Condition uncertainty niche demand shipping and repair costs. |

| Long term significance | Shows how failed commercial experiments can become fertile ground for cultural and technical reuse. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly were these computers and why should anyone care.

They were NABU machines that relied on cable based delivery of software and content. They matter because they represent one path computing might have taken. The modern internet emerged through many experiments. NABU is a case study in early attempts at distribution and in how infrastructure determines what ideas succeed.

Why did the owner choose eBay instead of donating to a museum.

Practical reasons often drive those choices. Clearing a heavy inventory from private property removes collapse risk. Selling on eBay is fast and places the items into many hands where they might actually be reused or repaired. Donation is noble but can be slow complicated and not guarantee broad technical engagement. In short there is a tradeoff between curated retention and distributed reuse.

Are these machines usable today.

Some are usable with effort. They were designed for hardware and network conditions that no longer exist. Hobbyists can emulate headend functions or build adaptors. For many the fun is the work required to get them running. For others they are parts or props. Usability depends on time money and technical patience.

Does selling these cheaply harm historic preservation.

It can. Every unit that ends up cannibalized is a loss. But the distributed model also allows for emergent conservation where enthusiasts rebuild and document functionality. There is no single correct stewardship model. A mix of institutional preservation and community driven resurrection often produces the richest outcomes.

How does this change how we think about old tech value.

It highlights that value is community determined and context sensitive. A device worth little to a museum can be invaluable as a teaching tool or as a parts reservoir. Low prices democratize access. High prices concentrate artifacts. Both have payoffs and both have losses.

Where can I learn more or get involved if I want one of these machines.

Start with retro computing forums museums and the York University Computer Museum archives which document the NABU project. Engaged communities often share documentation and emulators to help you bring hardware back to life.